The temptation, of course, is to give unnecessary emphasis to the politics of the time in the memoir, looking back with the luxury of hindsight, but Isherwood resists this and in both stories, the political situation in 1930s Berlin is there but only on the margins and when it is used as a core part of the story, it's done with humour.

And there is definitely humour in Mr Norris Changes Trains. Isherwood creates a character (in Mr Norris) who is fairly unique: highly emotional, fastidious, uptight, nervous, vain, but also charming. The narrator (as most of Isherwood's narrators tend to be) is distant, aloof, and we learn very little about him or his internal life. Again, though, what I admire about a tale such as this one is how the politics operates mainly off-stage. It's there. It affects the lives of the characters, but it's not the driving force of the plot. Like Sally Bowles, the story centers around one character and his means of survival in a hostile world.

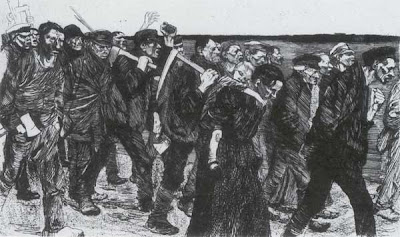

And there is definitely humour in Mr Norris Changes Trains. Isherwood creates a character (in Mr Norris) who is fairly unique: highly emotional, fastidious, uptight, nervous, vain, but also charming. The narrator (as most of Isherwood's narrators tend to be) is distant, aloof, and we learn very little about him or his internal life. Again, though, what I admire about a tale such as this one is how the politics operates mainly off-stage. It's there. It affects the lives of the characters, but it's not the driving force of the plot. Like Sally Bowles, the story centers around one character and his means of survival in a hostile world.There are colorful revolutionaries (who, for the most part, seem more interested in sleeping with one another than in actual politics), young Nazi ruffians, and suggestions that key characters may be spies or double agents or just corrupt charlatans. But Isherwood is mainly interested in the portrayals and interactions between his main characters: the ways they manipulate each other, the secrets they hold, the lies they tell. One very much gets the feeling that that book is not tied to its setting and could easily have been written/set 50 years earlier or 50 years later with only minimal changes.

That said, the book definitely represents in time and place insofar as Mr Norris is such a unique (and very British) character. It's a lovely little book and the kind of book one can read in a single afternoon without interruptions.